Rocks and Fossils and Zeolites, OH MY! A summary of the John Day Fossil Beds Field Trip

/Trip dates: September 25 - 27, 2025

Trip Leaders: Derek Loeb and Nick Famoso

Article by: Carole Miles

Photos by: Carole Miles, Lecia Schall, and Cindy Robinson

Early fall is a perfect time of year to explore the unique beauty of the John Day Fossil Beds area. We convinced 20 GSOC members, both newbies and seasoned veterans alike, that this was the case. So, on September 25 Derek Loeb, geology lead, Carole Miles, logistical lead, and Gary Joaquin, safety lead, met up with the group at the Clarno Unit picnic area. Following introductions, safety reminders, and distribution of field guides, we launched on the first activity — a short hike along the Geologic Time Trail to learn about the formation of and admire the striking Clarno Palisades. The Palisades are part of the Clarno formation — volcanic lava flows, tufts, lahars, mudstones, and conglomerates from the early to middle Eocene.

We returned to the picnic area for lunch and to meet up with Nick Famoso, Chief of Paleontology and museum curator for the John Day Fossil Beds National Monument. After regrouping at the Hancock Field Station, Nick led the group on a 2-mile hike to lay eyes and hands on the famous Hancock tree — thought to be a fossil Katsura tree, although some think a Sycamore or Poplar, that was entombed in its growth position during one of the many lahar events. We didn’t have time to visit, but discussed two other famous localities in this area: the Clarno Nut beds and the slightly younger Hancock Mammal Quarry. Starting in 1938 through the mid-1950’s, former GSOC member, Lon Hancock, following his retirement from the Postal Service, along with his wife, Berrie, and appropriately-named friend Tom Bones, made significant discoveries and collected fossils from both of these locales. The fossils found in the Mammal Quarry were mostly disarticulated, possibly indicating they were transported. The horse fossils found here have longer limbs than the horses of earlier time periods making them more suitable for running in the open habitats of the time. Abandoned wells sites can also be found in the area — remains from oil prospecting in the 1950’s and 60’s.

After loading back into our vehicles, we caravanned to our next stop, the Muleshoe Recreation Area, for a good view of the Picture Gorge Basalts and overall discussion of the John Day Basin geology. In 2020, Cahoon, et al. fine-tuned the dates of this unit to be 16.1 - 17.2 Ma, with 3 sub-units, 17 members, and 61 flows sourced from fracture systems near the town of Monument. The total volume of lava in the Picture Gorge basalts was about 1% of the total Columbia River Basalt volume. Derek also spoke about how columnar basalts form, and why the hexagon is the preferential shape found in nature — this shape can be arranged to cover a plane without gaps or overlaps, achieving the most uniform coverage.

With the sun getting low on the horizon, and hunger setting in, we continued on into Spray, our home base for two nights. We had rented the entire River Bend Motel (the only motel in town) and filled all the beds, with a few spilling over into local campgrounds. Lucky for us, a new drinking establishment, Ben’s Bar, had opened a few months before our arrival to complement the popular pizza truck for a bite to eat. The bar was constructed from an old silo and sits along the peaceful John Day River with seating both inside and out. We gathered to eat pizza, enjoy drinks, and pepper Derek with additional questions about the area geology and local history (including how the area, river, town came to be known as “John Day” — ask someone who went on this trip if you are curious to know!).

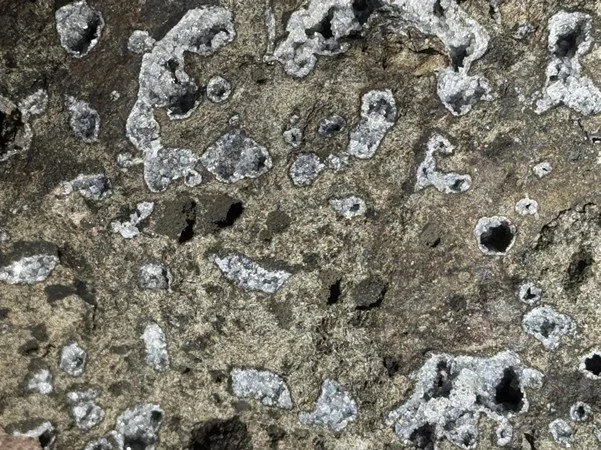

Our second day arrived with blue skies and the crisp fall air, giving us the opportunity to use the layered clothing we brought. We headed off to a location northeast of Spray to admire and collect zeolite mineral species (yes, distinct minerals are referred to as “species”). The Burnt Cabin Creek locality was first discovered by Al McGuiness in the early 1960’s and subsequently rediscovered by renowned zeolite specialist Rudy Tschernich. Julian Gray, our current GSOC president and renowned mineralogist himself (and friend of Rudy’s) suggested we add this excellent collection spot into our trip. Zeolites are a secondary, white-colored mineral, a product of weathering or alteration, that have commercial uses as absorbents and catalysts. They have an aluminosilicate framework with large channels or molecular cages within their structure. At Burnt Cabin Creek, twelve different species of zeolites have been identified in the Picture Gorge Basalt flow that lies just above the contact with the underlying John Day Formation. Here, the zeolites range in size from a few millimeters to several centimeters. Everyone left with beautiful samples.

We put away the rock hammers, as their use is not allowed anywhere within the John Day Fossil Beds Monument boundary, and headed south to the Sheep Rock Unit where we met Nick Famoso and his assistant, Jennifer, at the Visitor Center. Since the collecting of fossils within the monument is only allowed under the supervision of Monument staff, Nick had us all sign forms and participate in a brief training to become short-term volunteers of the Monument before we headed out into Blue Basin to see what we could find. Since no digging was allowed, we were scanning the ground and slopes for anything poking out of the beautiful blue soil of the Turtle Cove formation. This formation is composed of ash fall deposits from an eruption of the Crooked River Caldera in central Oregon, along with some deposits from the ancient volcanos of the Western Cascades. The ash subsequently weathered to clay minerals containing Celadonite, which imparts the blue color. Our efforts for just under a two-hour time period yielded two fossil teeth (one from an Oreodont, the other a rodent) and several small bone fragments. Four of the finds were worthy of keeping to add to the Monument collection, so we saw how Nick and Jennifer carefully document all pertinent information into their logs. It was a thrill for me, as well as several other participants, to be able to search for and collect fossils in the same locality that Oregon’s first geologist, Thomas Condon, made his important discoveries uncovering a nearly complete sequence of mammalian fossils that gave support to Darwin’s newly published work The Origin of Species.

Following lunch along the John Day River and under the gaze of Sheep Rock at Cant Ranch, we returned to the visitor center for a “behind-the scenes” tour of the museum collection and fossil processing room. Nick discussed the storage specifications, cataloging, and challenges associated with maintaining a significant collection which includes not only plant and animal fossils, but also other historical artifacts found in the Monument area, rock samples, photographs, and documents. He shared with us some of the fossils that the group was interested in seeing and discussed their significance. Jennifer led us through the process of how larger fossil finds are removed from the ground by first encasing them in a plaster jacket for transport. Then, once transported to the lab, the jacket is removed and the tedious process of slowly chipping away at the surrounding rock to uncover the fossil begins. When she began this work many years ago, it used to take her about 6 months to fully expose a mammal fossil that was about 2 feet in diameter. She can now do it in about a month. This is the favorite part of her job — being the first person to see and put her hands on a fossil that has been buried for millions of years! We all had the opportunity to try using the tool she employs for this work. Another part of her job is to make casts of fossils that researchers have requested from around the world. We had time to enjoy the Visitor Center exhibits and displays before we jumped back into vehicles for a quick trip to the Mascall Overlook.

At the Mascall Overlook, we took in the wide view of the Miocene deposits; the Mascall Formation, the Picture Gorge Basalts, and the Rattlesnake Formation including the distinctive Rattlesnake Ash-Flow Tuff. In addition to pointing out these formations, Derek explained why it is that the John Day River appears to be flowing east when it is actually flowing west…our brain is being fooled by thinking the road and the river are heading downhill to the east in the same manner as the Picture Gorge Basalts however, the road is actually climbing as you drive east and the river is flowing to the west. We returned to Spray for another evening at Ben’s Bar and the pizza truck (this time with a celebratory bridal party group!).

Day 3 had us caravanning west then south to our final destination — the Painted Hills Unit. Here you can see the colorful layers of ash and other sediments that tell the story of cycling periods of wet to dry climate as the warmer, wetter Eocene epoch transitioned to the cooler, more temperate Oligocene epoch. These are, again, the Bridge Creek and Turtle Cove assemblages. The tan/yellow colored layers indicate a cooler, dryer climate. The red layers indicate oxidation occurred in more temperate, warm, wet climates. The dark red is a highly oxidized soil from a very wet, hot, sub-tropical climate. The grey is a gleyed (sticky clay) soil from a reduced environment with little oxygen (a swamp or lake). Interspersed in these layers you’ll see black stripes and dots. These are manganese oxide nodules derived from manganese fixing plants. There is one hidden area, a favorite of Nick Famoso’s, with a very dark reddish-brown layer of laterite soil known as the “Brown Grotto”. This soil is very highly oxidized and leached, coming from a tropical, very wet, hot climate. Derek explained how these deposits weather to form various clay minerals with a platy structure. The smectites in particular absorb water and swell to become impermeable. Rain is simply shed as runoff making these paleosols inhospitable for most vegetation. Upon drying, they shrink and form a distinctive “popcorn” texture.

At our last stop, we took in the dug-out remains of Leaf Hill — a historically significant locale where, in 1923, a paleobotanist, Ralph W. Chaney, excavated a total of 20,611 leaf and seed fossils from the slabs of ashy shale found here. The bed again represents the variety of habitats found within the Bridge Creek assemblage, from Oak-Sycamore forest to Savannah Woodlands, including several periods of swamps and lakes, and finally Hardwood Forest, all capped by a hot ash fall. It was a satisfying place to end the trip, reflecting on these amazing assemblages of rock that tell the story of climate and evolution so beautifully, and the numerous geologists, paleontologists, and scientists who have (and continue to) piece together the story of the John Day basin.

Carole Miles